Materiality in Monetary Unit Sampling is a crucial concept that guides auditors in focusing their efforts where it matters most. This blog post will explore how materiality influences the audit process within this sampling framework. We will discuss how auditors determine materiality thresholds and the impact these have on assessing financial statement accuracy. Understanding this principle helps ensure that audits are efficient and effective, concentrating resources on the most significant areas.

Definition of Materiality in the context of Monetary Unit Sampling

In the context of monetary unit sampling (MUS), materiality refers to the significance of misstatements in individual dollar (or any other currency) amounts within an account balance. The auditor uses materiality to determine the level of misstatement that would be considered significant within the context of the overall financial statements. Materiality is crucial in MUS as it helps the auditor assess the impact of misstatements on the financial statements and make informed decisions about the adequacy of the audit evidence obtained through sampling.

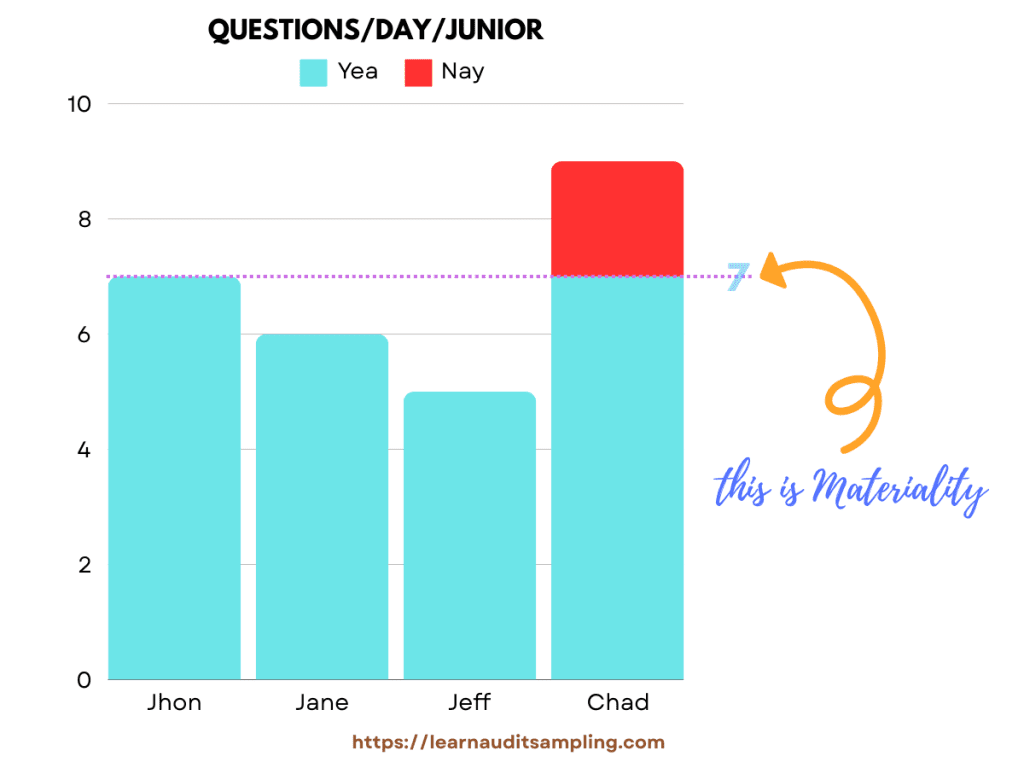

Imagine you have several junior auditors you must train. After a few days, you realize that some juniors are easier to work with than their peers. Bored, you decide to create a Yea or Nay test. If someone asks more than seven questions per day, (s)he (or they) will fall into the “nay” category. Conversely, the “yea” category is for those who ask seven questions at max.

Seven is your materiality.

At the end of the week, you gather your mini-research data. The following image displays the results.

Apparently, this “Chad” person falls into the “Nay” group. And fortunately, the rest is within the acceptable area.

The “materiality”, the data, and the conclusion give you enough foundation to recommend to the audit manager, either to fire him or give him special treatment.

The seven questions/day/junior is your “materiality” to discriminate between yea or nay person. Although not identical, it shares some commonalities with the materiality in the Monetary Unit Sampling.

- Both are a number. Precisely the maximum number you are willing to accept before changing your opinion about someone or something.

- Both discriminate between two categories/groups—for example, Yea or Nay, (the financial statements is) materially misstated or not materially misstated.

- You decide the number before doing the test/procedure. In the audit realm, you pick the materiality in the audit plan stage. However, ISA 320 or AICPA AUC-C section 320 says that you can revise the materiality during the audit progress.

- The number depends on your

subjectivityprofessional judgment. For instance, in the previous junior training session, you felt ten questions/day/junior was too much, so you reduced the number this time. In the context of materiality in the MUS context, there are several variables, such as the nature of the industry and/or entity, the auditee’s control environment, and several other factors. The following section will cover the factors you must consider to determine materiality.

Overall Materiality

That’s the big idea of materiality in audit (especially in the MUS context). The concept of materiality is crucial for you because it’s the level of misstatement in the financial statement that would influence the decision of the financial statement users. The materiality set for the financial statement, as stated by some authors like Arens or Whittington, is called overall materiality.

As a note, you also break down the materiality to the account balance’s level.

Performance Materiality

As an auditor, you may want an early warning score, which tells you when the aggregate misstatements may exceed the overall materiality. That’s the performance materiality.

If you remember about the tolerable misstatement, that’s the application of performance materiality (to a particular sampling procedure). The tolerable misstatement for an account, balance, or class of transactions is normally set at or less than performance materiality (AICPA’s Audit Guide: Audit Sampling).

The complete story about this materiality is for another day; for now, we’ll content ourselves with the knowledge that the performance materiality gives you wake-up calls when certain areas may contain a significant misstatement; thus, you can focus on it.

Now, back to the materiality (both overall and performance materiality).

When using MUS, you calculate the projected misstatement (upper error limit) for the misstatement you found in the account balance(s). You then compare the founded misstatement with the materiality. Yes, technically, tolerable misstatement is used, but since it’s an application of performance materiality, in this case, both materiality and tolerable misstatement can be used interchangeably.

Don’t forget about the sample size. It’s also determined by the materiality you choose. You can pick whatever method to calculate the sample size, but you’ll need the tolerable misstatement number as a factor.

Factors Influencing Materiality Decisions

How do you choose the “right” materiality levels?

As usual, there are no “righty right” materiality levels. You (or your firm) must consider several factors, such as the account balance’s importance, the item’s nature, prior experience, account balance trends, and other criteria. You also consider the effect of any misstatements on users’ decisions, such as the impact on profit figures, ratios, external influences, and difficulties in raising finance.

The materiality level is determined based on professional judgement.

(Here is our favorite quote)

Don’t forget that in auditing, materiality is determined by considering the needs and expectations of the financial statement users rather than those of the auditor.

On the other hand, materiality is a critical factor in the entire audit process, which influences your decisions at various stages, from planning to completion. It is used to assess the significance of misstatements, evaluate the reasonableness of financial statements, and determine the appropriate audit opinion to be issued.

Those internal and external factors influence your decision of materiality level.

Here are several guidelines for deciding the materiality level for your next audit assignment.

- Financial statement users’ needs and expectations: Overall materiality is determined based on the common financial information needs of the users as a group.

- Nature of the entity: The entity’s size, nature, and complexity can influence the decisions of the materiality level. For example, what may be material for a small company may not be material for a large multinational corporation.

- Risk of misstatement: The auditor assesses the risk of material misstatement at the financial statement and assertion levels to identify where misstatements may occur and to determine the impact on materiality.

- Control environment: The effectiveness of the entity’s internal controls, including any deficiencies or weaknesses, can impact materiality decisions.

- History of misstatements: Previous instances of identified misstatements in prior period audits can influence the materiality threshold for the current audit.

- Accounting issues and estimates: In accounting issues, significant judgment and estimation uncertainty can affect the materiality level decisions.

- Turnover of key personnel: High senior management turnover or key financial reporting personnel may impact materiality decisions.

- Entity operations: The number of locations the entity operates can also factor in materiality decisions.

Challenges in Applying Materiality in Monetary Unit Sampling

Determining the materiality level, for example, the tolerable misstatement levels, can be challenging as it requires judgment and consideration of various factors. Below are some of the challenges.

- Disaggregating overall materiality: Determining overall materiality for the financial statements as a whole is a professional judgment. Disaggregating overall materiality and allocating resulting amounts to smaller components, such as accounts, systems, or individual tests, can be challenging.

- Allocation to accounts: Allocating materiality to different accounts based on each account’s balance relative to the total is a starting point, but adjustments may need to be made for the risks associated with each account. This method takes into consideration both the size of the account balance and any particular risks, but it requires careful consideration and judgment.

- Identifying Expected Misstatement: Estimating the expected misstatement in the population can be difficult, especially in complex or large populations where the nature and extent of potential misstatements are not easily discernible.

- Relationship between materiality and testing: The level of materiality has a direct effect on the amount and type of evidence and testing needed. Determining the appropriate level of testing based on materiality requires careful consideration and professional judgment.

- Precision of testing: The level of materiality determines the precision of testing. If materiality is small, testing must be to a higher level of precision, which can pose challenges in terms of resource allocation and time management.

- Cumulative net impact of errors: If the cumulative net impact of known errors exceeds overall materiality, auditors must consider whether to insist on the correction of the accounts by the client or qualify their audit opinion. This decision involves careful consideration of the materiality thresholds and their implications.

- Conservative Evaluation Methods: The evaluation methods used in monetary unit sampling are inherently conservative when misstatements are found. This can result in producing bounds that are far in excess of materiality, making it difficult for auditors to effectively assess the impact of misstatements.

- Large Sample Sizes: In order to overcome the issue of conservative misstatement bounds, large samples may be required. This poses a challenge as it increases the time and resources needed for the audit process.

- Expectation of Misstatements: When zero or few misstatements are expected, the evaluation methods in monetary unit sampling may still produce bounds that are too high to be useful to the auditor. This can make it challenging to effectively apply materiality in the sampling process.

- Use of Statistical Conclusion: While providing a statistical conclusion is considered an advantage of monetary unit sampling, it can also pose a challenge in terms of applying materiality. The statistical nature of the conclusion may require a deeper understanding of statistical concepts and their application to materiality assessment.

- Specific Identification Testing: There may be challenges in determining when to rely solely on specific identification testing and when to use monetary unit sampling, especially in cases where specific identification testing is not considered effective and/or efficient.

- Qualitative considerations: In addition to evaluating the frequency and amounts of monetary misstatements, the auditor should consider the qualitative aspects of misstatements, which adds complexity to the assessment process.

- Compliance with auditing standards: Applying materiality in monetary unit sampling requires adherence to auditing standards and guidelines, which may present challenges in ensuring that the sampling process aligns with professional requirements and best practices.

- Documentation and communication: Effectively documenting the rationale behind materiality decisions and communicating the implications of sampling results to relevant stakeholders can be challenging, especially in complex audit engagements.

Conclusion

Materiality in Monetary Unit Sampling shapes how auditors prioritize and address financial statement inaccuracies. It ensures focus on the most impactful areas, improving audit efficiency and effectiveness. Proper application of materiality helps auditors avoid unnecessary work on inconsequential details, focusing instead on significant errors that could affect stakeholders’ decisions.

By setting appropriate materiality thresholds, auditors can provide better assurance about the financial health of an organization. This approach saves time and enhances the credibility of the financial statements. Auditors must remain vigilant, continuously assessing materiality throughout the audit to respond to new information or changes in the entity’s situation.

Stay ahead in your auditing career by keeping up with essential concepts like materiality. Subscribe to our newsletter for more insights and updates on best practices in auditing. Join our community of professionals today and never miss an update on tools and tips that can refine your auditing skills.